Did you know that millennials make up 35 percent of the workforce in the United States, but only about 24 percent of state and local health departments? This is despite a 300 percent growth in public health degrees over the past two decades. So where are the millennials, and what do these numbers mean for the future of public health?

Public health’s greatest asset is its people, but the workforce is rapidly aging and facing tremendous turnover. In fact, according to the Public Health Workforce Needs and Interests Survey (PH WINS), as many as 41 percent of public health employees in state and local health are considering leaving in the next five years.

At the recent annual meeting of the American Public Health Association, the de Beaumont Foundation hosted a session on millennials in the public health workforce that revealed important trends, challenges, and opportunities. Moderated by Brian C. Castrucci, DrPH, MA, CEO of the de Beaumont Foundation, the panel discussion featured four millennial leaders:

- Elizabeth (Lizzie) Corcoran, MPH, CPH, Special Assistant to the CEO, de Beaumont Foundation

- Brittany K. Marshall, DrPH, CPH, CHES-Evaluation Specialist, CDC Foundation

- Ryan Tingler, MPH, Research Project Manager, University of Pennsylvania, School of Nursing

- Colleen Healy Boufides, JD, Senior Attorney, National Network for Public Health Law

In dialogue with each other and the audience, four key insights emerged.

1. Millennials are cause-driven and motivated to work for many of the fundamental principles that underpin public health.

Citing research by The Millennial Impact Report, Colleen Healy Boufides highlighted one of the key characteristics of the millennial workforce: millennials are motivated to work for causes they feel passionately about, not by loyalty to institutions or the way things have traditionally been done. Social justice issues like LGBTQ rights, income inequality, minimum wage debates, and affordable housing / gentrification compel millennials to spend their most precious asset – their time – in service of causes that make the world a better place.

Public health, and especially the focus on the social determinants of health, is a natural fit for cause-driven millennials. Looking at how “the distribution of money, power, and resources at global, national, and local levels” influences the health of individuals and communities falls squarely within the lexicon of the millennial generation and can serve as a clarion call to this group.

Healy Boufides’ own story reflects this trend. After reading about Paul Farmer’s work in Mountains Beyond Mountains, she was inspired to pursue a career focused on health inequities. While her intended field of work shifted several times, from healthcare to public health to law, her desire to work on health inequities remained a constant.

“I started out moving toward a healthcare career,” she said, “but then I realized I wanted to work on the causes rather than the symptoms of health inequities. I started focusing on public health, and then I realized all of those causes could be changed through law and were affected by law, so I decided to go to law school specifically to work on public health.”

Before you can be motivated to pursue a career in public health, you have to be aware of the opportunities – which leads to the next key insight.

2. Millennials see networking and mentorship relationships as valuable both for career opportunities and professional development – and older generations should see this as a critical path to engaging young talent in the public health workforce.

The importance of networking and mentorship was the subject of Ryan Tingler’s presentation, and a recurring theme of the other panelists. Tackling a common misconception about mentoring, he emphasized that mentoring is a two-way street, with benefits for both the mentor and the mentee.

Brian Castrucci, Lizzie Corcoran, Brittany Marshall, Ryan Tingler, and Colleen Healy Boufides

For the mentee, the benefits are obvious: a mentor can share valuable professional skills, provide career insights, and open doors to new opportunities. The mentor also stands to benefit from engaging deeply in this professional relationship. The mentee may bring new knowledge or approaches to longstanding problems, and the mentor may garner new insights into how his or her younger colleagues see the world around them.

“It’s a two-way street,” said Tingler, “and it’s not just about the technological side of it. It’s about recognizing generational and cultural changes.”

For career public health officials, mentoring is also an invaluable tool for recruiting new talent into the public health workforce. That mentoring can be as simple as pointing out possible career opportunities in public health that a student had never heard of or introducing a research fellow to a leader in his or her field at the APHA Annual Meeting. Mentorship and networking can also help talented individuals from other industries to see how they might apply their skills in evaluation or education, for example, to a rewarding role in public health.

Mentors will find that millennials are largely eager recipients of their guidance, Tinger said. Tingler shared results from a survey of the APHA Student Assembly that demonstrated a broadly shared desire for more mentorship and stronger networks. As Tingler said, “We don’t want you [the older generations] to go – we want you to teach us.”

3. Millennials seeking careers in public health face significant barriers to entry – and public health should strive to support millennials (and younger workers) through entry-level fellowships, debt forgiveness packages, and other incentives.

Lizzie Corcoran highlighted a seeming incongruity between two datasets: one, the explosion of interest in public health degrees by millennials; and two, the underrepresentation of millennials in the governmental public health workforce. Many audience members shared their experiences as a possible explanation for why, including:

- Outdated hiring requirements that require nursing or medical degrees to do public health work

- The concentration of job opportunities in major metropolitan areas

- The financial pressures of graduating with significant student debt

In her presentation, Brittany Marshall, DrPH, provided insights into one avenue for transitioning promising students into governmental public health: fellowships and professional associations. In her already-impressive career, Marshall has participated in the Public Health Associate Program (PHAP) at CDC, the CDC Evaluation Fellowship, and the APHA Student Assembly on national and state levels. Marshall has also pursued development opportunities outside of public health, such as the National Urban League Emerging Leaders program, the New Leaders Council, and LEAD Atlanta.

Fellowships are not only valuable, paid learning opportunities for the entry-level and early career workforce. They also allow fellows to create strong networks with their peers and current public health leaders that can open doors to the next career opportunity.

Marshall’s advice to millennials and the younger generation is to “make sure you’re always networking… you never know who you’ll meet. Ninety percent of my opportunities have been through a personal connection.”

Fellowships are only part of the puzzle. Corcoran identified several other strategies to help the public health workforce attract millennial talent, including:

- Streamlining hiring processes and making job descriptions clearer

- Collaborating with academic health departments

- Actively marketing career opportunities to students of public health

None of these fully address the ongoing student debt crisis in the United States, though. Ultimately, governmental public health will have to ensure that it’s financially viable for the average graduate to pursue a career in public health (by adjusting salaries or guaranteeing student loan forgiveness) or risk losing a generation of talent to the private sector.

4. Millennials are ready and able to infuse the public health workforce with new energy – but the workplace has to be ready for them.

Millennials are graduating with public health degrees in record numbers and are passionate about making the world a better place. They’re digital natives, highly collaborative, and strong communicators, and they prize innovation and interdisciplinary action above tradition and siloed work. Not only that – they want to learn, from their peers as well as from their superiors.

As Corcoran shared from her own experience as well as her ongoing research on the millennial workforce, “Millennials have a lot of unique contributions to make to public health. We are passionate about public health, we are studying public health in order to practice it, and we’re passionate about our communities.”

The public health workforce should be welcoming millennials into their ranks with open arms, and yet clearly something is happening to discourage public health graduates from moving into the governmental workforce. With the millennials’ passion for public service, money is not the only barrier to entry, although it is a clearly a contributing factor.

The current public health workforce should see a clear path to engaging with millennials: reach out to talented individuals (even if they’re not currently working in public health!), communicate the mission of public health, and identify opportunities for them to bring their talents to bear.

Millennials are ready and able – now it’s time for the public health workforce to catch up to them!

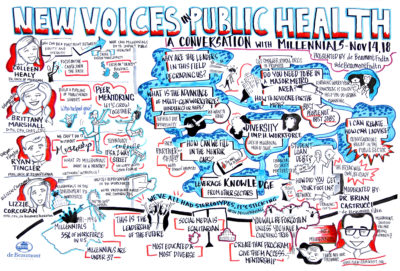

Click image for the visual notes from this session, by Lauren Green, @dancing_markers:

Read more:

- The New Public Health Generation: A Sales Pitch for Governmental Public Health

- New Voices: Millennials and the Future of Public Health

To receive updates on our ongoing research into the public health workforce, including a forthcoming paper on millennials in the public health workforce, subscribe to our newsletter.